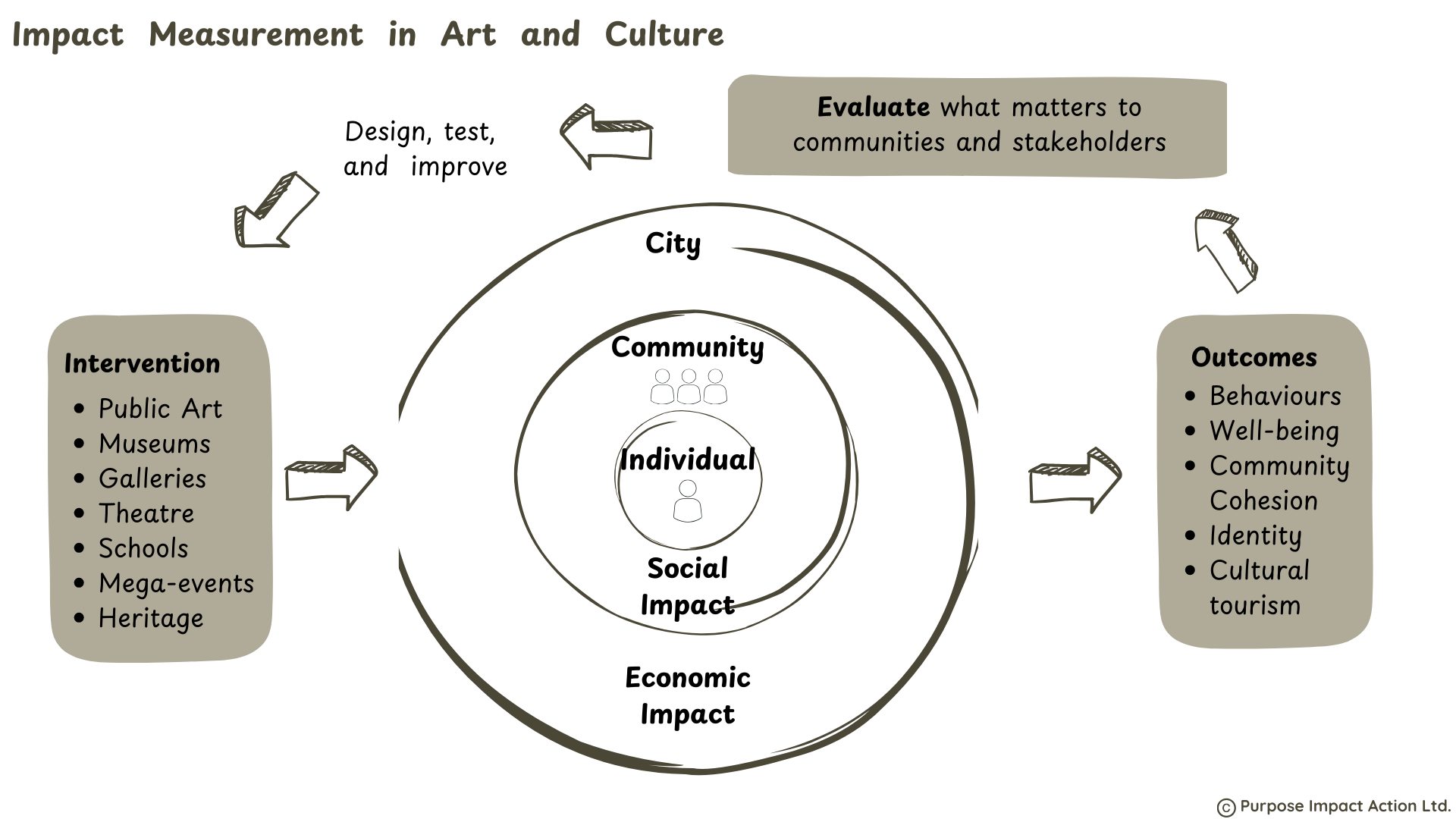

Language is more than a medium for communication — it shapes how we understand, measure, and drive social impact. In the multicultural landscape of Hong Kong, language plays a crucial role in shaping social impact discourse. How do we ensure that key social impact, often imported from global contexts, truly resonates in Hong Kong’s unique context?

Investigating the challenges of social impact measurement in Hong Kong, Purpose Impact Action (PIA) is publishing a series of articles on local adaptation of social impact measurement practices in Hong Kong. In this conversation, Pia Wong, founder of Purpose Impact Action (PIA), and Victoria Wong, PIA consultant and ESG specialist, discuss the everyday realities and deeper tensions behind the local adaptation of social impact measurement in Hong Kong, and how translating the language of social change is both a challenge and an opportunity.

Pia: Victoria, you’ve spent a lot of time navigating the language of social impact in Hong Kong. What are some challenges you’ve faced when translating our white paper?

Victoria: While working on our white paper (link), I noticed that Hong Kong lacks homegrown, Chinese-written research on social impact. The terms for social impact measurement vary widely across universities, NGOs, and think tanks. Some use “社會影響評價,” “社會效益評估,” and others, often used interchangeably. “影響” can mean influence, effect, or impact, while “效益” means benefits. Eventually, I found “social impact assessment” (SIA) as was one of the 96,000+ official terms under the Civil Service Bureau’s e-glossary. The struggle to find standardized terms for social impact measurement reflected a deeper uncertainty about what “impact” truly means in the local context.

Pia: Why do these inconsistencies exist?

Victoria: It’s a mix of historical, regional and cultural context. Hong Kong is a melting pot of cultures with a colonial past that has shaped its linguistic landscape. Legal documents often state, “English version prevails when in doubt.” Chinese itself is complex, with traditional and simplified scripts across regions, and we also have local Cantonese slang. Social development concepts might be more progressive in other regions; as these concepts are still emerging here, conversations often default to English when Chinese terms are lacking.

Pia: How does this play out across different sectors—say, between nonprofits and businesses?

Victoria: Every sector has its own vocabulary. Nonprofits use community-centered or advocacy-based language, while businesses might frame things in terms of “corporate responsibility” or “shared value,” often guided by compliance or branding. This can cause confusion, especially when the different sectors work together but do not speak the “same language.” For example, nonprofits may prefer the term “ethnically diverse communities” over “ethnic minorities” to advocate for the demographic served, but this is not part of the government’s official language (which uses the latter term.) What we’re also seeing now, in the business sector, is how the conversations around ESG (environmental, social, and governance) have been influencing the language of impact, which fundamentally changes the focus of the conversation.

Pia: How is ESG reporting shaping the language of social impact in Hong Kong?

Victoria: ESG Reporting Code, a mandatory disclosure framework for listed companies, has accelerated the adoption and development of social impact language. We’re seeing conversations and panels being led by multinational companies, most of them in English, to discuss topics around the topics of environmental and social impact. While this drives dialogue, ESG reporting is ultimately driven by compliance and risk mitigation. The ESG Code is also heavily environment-focused, which can frustrate the social impact practitioners when trying to align with corporate standards.

“This raises the question: should the corporate sector be the main driver for defining our social impact terminology?”

Pia: Do you see a tension between compliance-driven and values-driven approaches in the sector?

Victoria: Yes, and it’s a real challenge. Compliance can help align organizations and push change, but we have to ask if actions are driven by genuine commitment or just a need to tick the box. The tension between ESG (compliance-focused reporting) and CSV (Creating Social Value) reflects the challenge and reality of the impact sector, and it’s something I discuss further with Jonathan Mok, a DE&I practitioner, in our next blog.

Pia: Is there a “right” Chinese term we should be using in Hong Kong’s social impact sector?

Victoria: There’s no right or wrong answer. In a sustainability course I took, the professor advised: “when in doubt, use the English version,” explaining that Hong Kong is still early in developing sustainability practices and its language, ESG reporting has since made language more consistent, but regional differences still exist and the city seems comfortable with a blend of terms for now. Chinese is a direct language, so the meaning of different terms aren’t necessarily confusing.

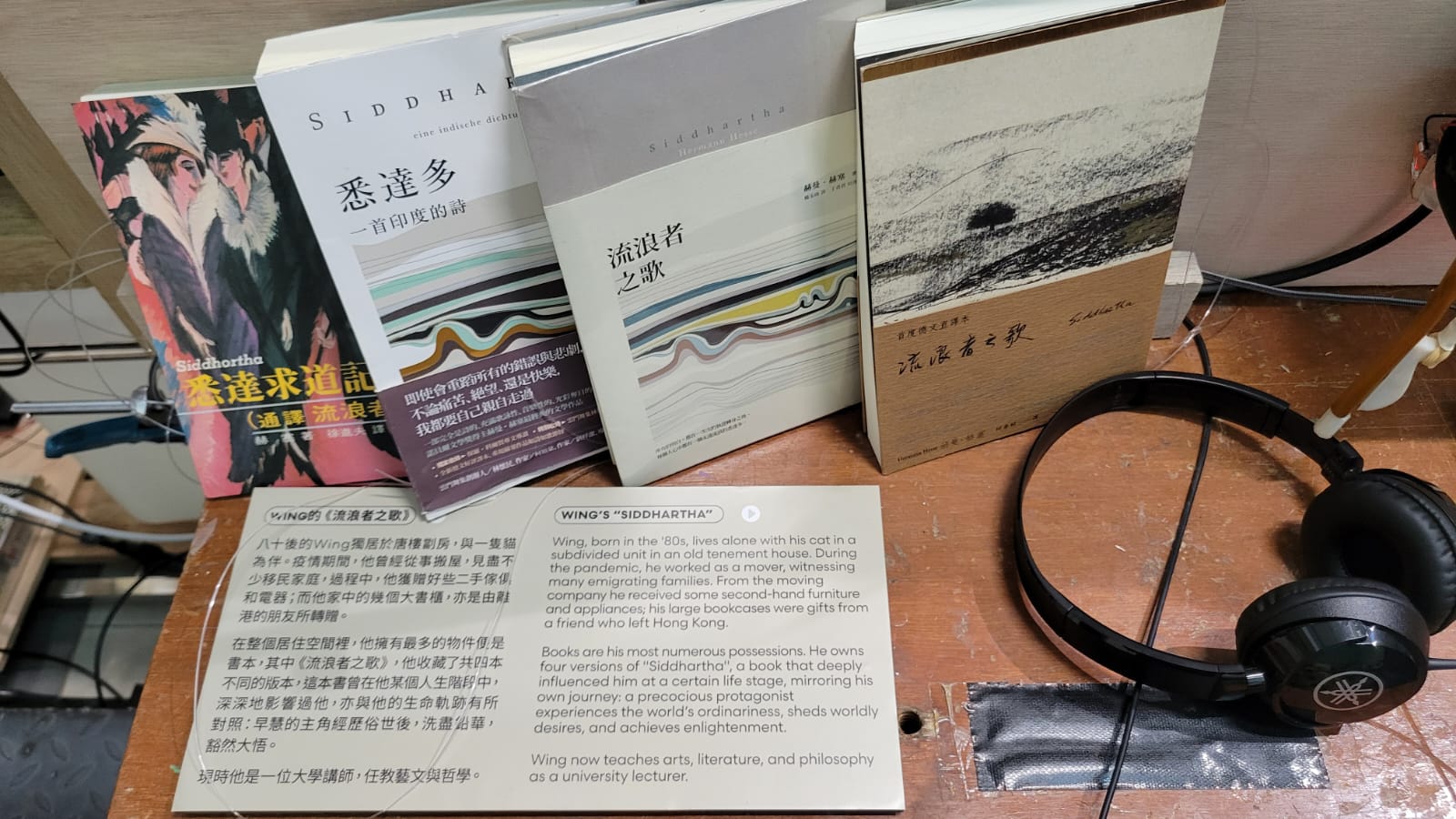

But if we go back to social impact measurement, Hong Kong does lag behind in adoption. Whereas many have adopted social impact measurement, the official language shows that we’re still talking about “assessment.” In Chinese, you can use either 評估 or 評價 for the word “assessment”, but there are nuances. “評價” can also imply value judgment or cost (the last character, 價, is associated with cost or monetary value.) The words we choose reflect our values in how we approach impact.

Pia: Could you explain the challenges of translating global concepts into the local context?

Victoria: Gender equity is a great example of why local adaptation is more than just translation. In developed English-speaking countries, the conversation has evolved from gender equality (“getting women a seat at the table”) to gender equity (ensuring equal opportunities). But in Chinese, with our cultural context of hierarchy and traditionally defined roles, the metaphor “getting a seat at the table” just doesn’t translate – it doesn’t inspire the same kind of action and meaning. (I will be diving deeper into the concept of gender equity in a future article) We can have a word for everything, but just having the translation isn’t enough if the context doesn’t translate.

Pia: How does terminology development reflect social priorities?

Victoria: I sometimes joke that you can tell how much Hong Kong cares about an issue by looking at whether there’s a Chinese term. ESG regulation has accelerated language for the “E” (environmental) issues, but the “S” (social) lags behind due to less regulation. More public discussion are needed to shape our social impact vocabulary.

Pia: Who should be responsible for defining standardized Chinese terms for social impact in Hong Kong?

Victoria: It needs to be a wider conversation that involves practitioners, academics, nonprofit professionals, business leaders, and the government.

“In Hong Kong, there’s a wide assumption that change can only happen from the top down, but what we’ve seen from the social sector is that influence comes from the bottom up. Making change is a collaborative effort.”

Pia: What practical steps can we take to move this conversation forward?

Victoria: First, we need to agree on some basic terms — such as whether to use “影響” or “效益” for “impact” and “benefits” when it comes to social impact. Then, we need to localize concepts within Hong Kong’s real-world context. Even though the Civil Servant Bureau has a huge glossary (close to 97,000 words!), there’s no standardized terms for social impact. Just as there’s a gap, equally there is an opportunity for us to collaborate.

What steps do you think we, as a sector, can take to move toward a shared language for social impact in Hong Kong?

By Victoria Wong, Consultant, Purpose Impact Action

Share your thoughts in the comments below