The path to inclusive language and social impact in Hong Kong is complex. It requires more than just translation—it calls for cultural adaptation, compelling business cases, and practical relevance.

In our previous article, we examined the complexities of translating social impact concepts in Hong Kong, and how language shapes the sector’s understanding. Today, we look closer at what’s at stake when language choices affect how people see differences and inclusion. Purpose Impact Action (PIA) consultant Victoria Wong speaks with Jonathan Mok, a DE&I and neurodiversity advocate, about why words matter, how language can reinforce or challenge stigma, and what it takes to drive authentic inclusion in Hong Kong’s pragmatic, compliance-driven society.

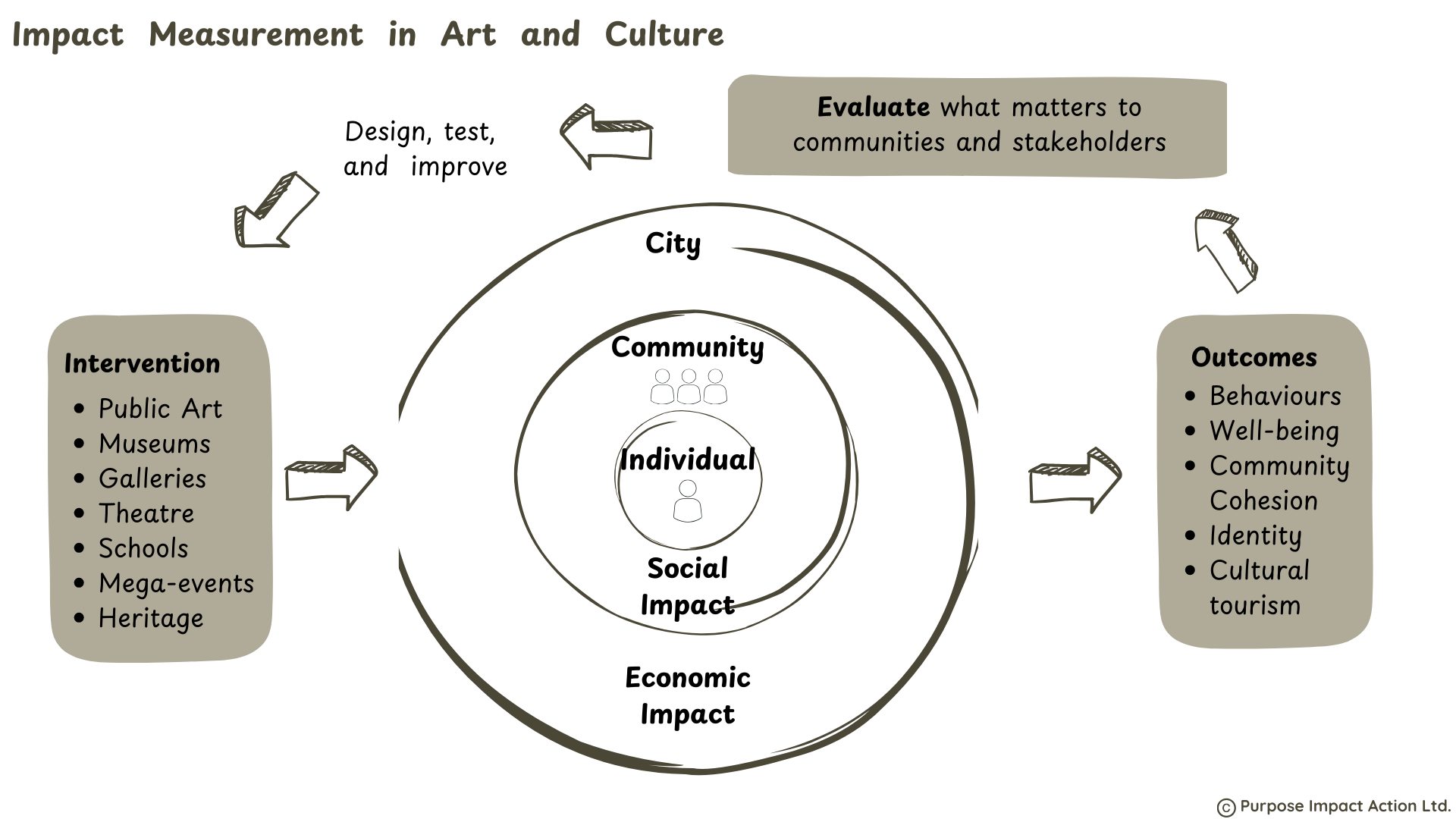

This article is part of PIA’s blog series on the local adaptation of social impact measurement in Hong Kong.

Victoria:

Jonathan, you’ve been an advocate for neurodiversity for many years. I’ve always appreciated how insistent you are about discussing neurodiversity bilingually, in English and Chinese, both in person and online. However, talking about neurodiversity or social impact in Chinese must not be easy. Could you share how you navigate language choices, especially given the nuances of the language and translations?

Jonathan:

When I talk about neurodiversity, I speak with the term “神經多樣性,” which originated in Taiwan and is widely adopted within the community as a literal translation—“neural” (“神經”) and “diversity” (“多樣性”). However, some organizations use “腦力多元,” emphasizing the power and diversity of the brain. The difference is subtle but important: the first emphasizes diversity of the neurological system, while the second focuses on brainpower.

Victoria:

What’s the debate behind these two terms?

Jonathan:

Some worry that the first term carries stigma, as it sounds associated with “神經病,” a derogatory term for mental illness, meaning “crazy.” That’s why some organizations advocate for the latter, believing it reduces negative associations and helps destigmatize neurodivergent conditions.

Last year, the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital adopted “神經多樣性,” the term I use, as the official translation for neurodiversity. But apart from the Hong Kong Children’s Hospital, there’s still no consistent, government-approved term in traditional Chinese for neurodiversity in Hong Kong.

Victoria:

When I was researching translations for PIA’s whitepaper on social impact assessment (link), I struggled to find standardized terms for social impact measurement. Eventually, I found the Civil Service Bureau’s e-glossary, which has close to 97,000 definitions from all public sectors. “Social impact assessment” was one of the official terms under the Town Planning Department (not Social Welfare), translated as “社會影響評估,” which I decided to use. Even then, this term varies widely across universities, NGOs, and sectors. Do you see similar inconsistencies in the field of neurodiversity?

Jonathan:

Yes, and there are a couple of reasons for this inconsistency. Some in the medical community still consider autism to be an illness, which leads to resistance against terms like neurodiversity—they see it as language control. Others are more comfortable with “special education needs” (SEN), though that is not completely accurate either. SEN often gets conflated with learning disabilities and neurodivergence, but actually, it also includes those with physical disabilities.

Victoria:

Why do you think there are such inconsistencies?

Jonathan:

There’s an assumption in Hong Kong that change has to come from the top down. When the government and official bodies adopt a term, it quickly becomes the norm. So iIf the government provided a clear definition for neurodiversity in Chinese, people would follow. But right now, there isn’t one. Many NGOs feel safest aligning with official terminology, as it’s seen as the least controversial path.

There are also regional differences. In Taiwan, autism and ADHD are still classified as childhood-onset mental disorders, which is why advocacy groups there push for the term “neurodiversity” (“神經多樣性”). Some say the term chosen in Mainland China—where neurodiversity is defined and used by the government and hospitals—will influence how the term is used in Hong Kong.

Victoria:

That slow evolution of language around “illness” is something I’ve noticed too. Globally, while the term “mental illness” is increasingly phased out by the more inclusive term, “mental health condition” or just “mental health,” in Hong Kong, this adaptation seems slow. Do you have a similar observation in the neurodivergent community, and what is a more inclusive term to use in Hong Kong?

Jonathan:

Just as we say “condition” in English, I use the word “特質” (quality), which focuses on unique traits rather than illness. This wording is also more palatable for the medical community; however, it is not a natural way to describe a condition, and it will take a while for mainstream society to accept it. Language reflects social class as much as anything else. For example, at a workshop I recently gave for frontline staff at a logistics company, someone referred to autism as an illness. Given her background, I could understand why she might not use the word “condition.” But in professional settings, neurodiversity is more commonly used.

The Disconnect in Impact and ESG’s Influence

Victoria:

On the topic of professional settings: conversations around ESG (Environmental, Social, and Governance) seem to be shaping the language around social impact in Hong Kong. We see many multinational companies driving these discussions—many of which are only in English. For example, there seem to be far fewer discussions about gender equity in Cantonese, and when they do happen, it’s usually on a smaller scale. What are your thoughts on this?

Jonathan:

There is a disconnect between Western-educated, English-speaking and locally-educated, Chinese-speaking professional world. Locally, progressive agendas like diversity, equity, and inclusion (DE&I) are often linked to compliance. Hong Kongs society is pragmatic, especially in business. People want direct, practical language. Even when the language sounds progressive, the values remain conservative. The concepts themselves don’t always translate culturally. We have to remember that many people in Hong Kong grew up with a conservative upbringing; most local schools are managed by religious organizations, shaping social attitudes.

Victoria:

Is that because global concepts are hard to localize? For example, “having a seat at the table” is widely accepted in first-world, Western contexts, but may not directly translate or resonate with the mainstream society in Hong Kong. This is something that I am digging deeper into, in a future article.

Jonathan:

Partly. There’s also a perception that those advocating for gender equality are global elites, and not really connected to the local mainstream community. Local practitioners see this disconnect and try to bridge it, but introducing inclusive language can be tough. Mainstream society is more open to DE&I in education and employment, less so when it comes to inclusive language for gender or sexual equality. When I started this work, mentors advised me to link neurodiversity to education or employment. People will listen, as it encourages social mobility.

“Hong Kong is pragmatic, especially in business. People want direct, practical language. Even when the language sounds progressive, the values remain conservative. The concepts themselves don’t always translate culturally.”

Victoria:

There seem to be many factors—language, culture, religion, and socio-economic status—which all affect how social impact terms are adopted. Noting Hong Kong’s tradition in driving change through compliance, like with environmental or discrimination laws, do you think ESG regulations can help make the language more consistent?

Jonathan:

ESG is often meeting the government’s standards. It’s about systems and discipline. Many believe compliance should not be forced as it can hurt profits, but without it, few companies take action. Language-wise, people like the word and concept of ESG – it’s easy to understand.

Nonetheless, instead of ESG, I wish there were more people talking about CSV (Creating Shared Value) which is more about solving social problems while running a business. People buy in because they see real impact, not just compliance. Social enterprises often start with CSV, however that’s not always sustainable; success depends on leadership, business strategy, and community ties.

Decrypting Social Impact

Victoria:

I want to go back to the topic of language, which has a huge influence on shaping our attitudes and beliefs. Is it what you’re trying to achieve with bilingual Linkedin posts?

Jonathan:

The main driver for me is diversity and inclusion. If you see my photos, I make a point to add alt-text to make them accessible for the visually impaired. Frankly, I don’t know the best way to write alt-text, but I just know I have to start doing it. My personal challenge is using fewer emojis—which I like to include in my text—because they are not accessible for visually impaired readers. For people who use a screen reader, emojis appear only as text.

Victoria:

That’s really helpful to know, thank you for sharing. I appreciate that you’re “walking the talk.”

Jonathan:

I think the hardest part now for me is time. When I used to make a LinkedIn post, it would take me 15 to 20 minutes; now I spend 45 minutes to an hour writing one post. First, I have to make it bilingual. Then there are hashtags, the alt-text behind each photo, and formatting. I post less than before—now, about once every four days. I just block my time to do it.

Going back to the challenges of adopting DE&I, companies may see this increased use of time as a cost of adoption, which means higher resource allocation. At the end of the day, Hongkongers are realistic. Social change needs to come with tangible benefits.

Victoria:

The word “benefits” reminds me of the two main terms I see around social impact measurement in Chinese – 社會影響評估, which focuses on assessing impact, and 社會效益評估 which focuses on benefits. Neither term is right or wrong, but this term does lack consistent terminology. How do you explain it to people who find the language and concept abstract?

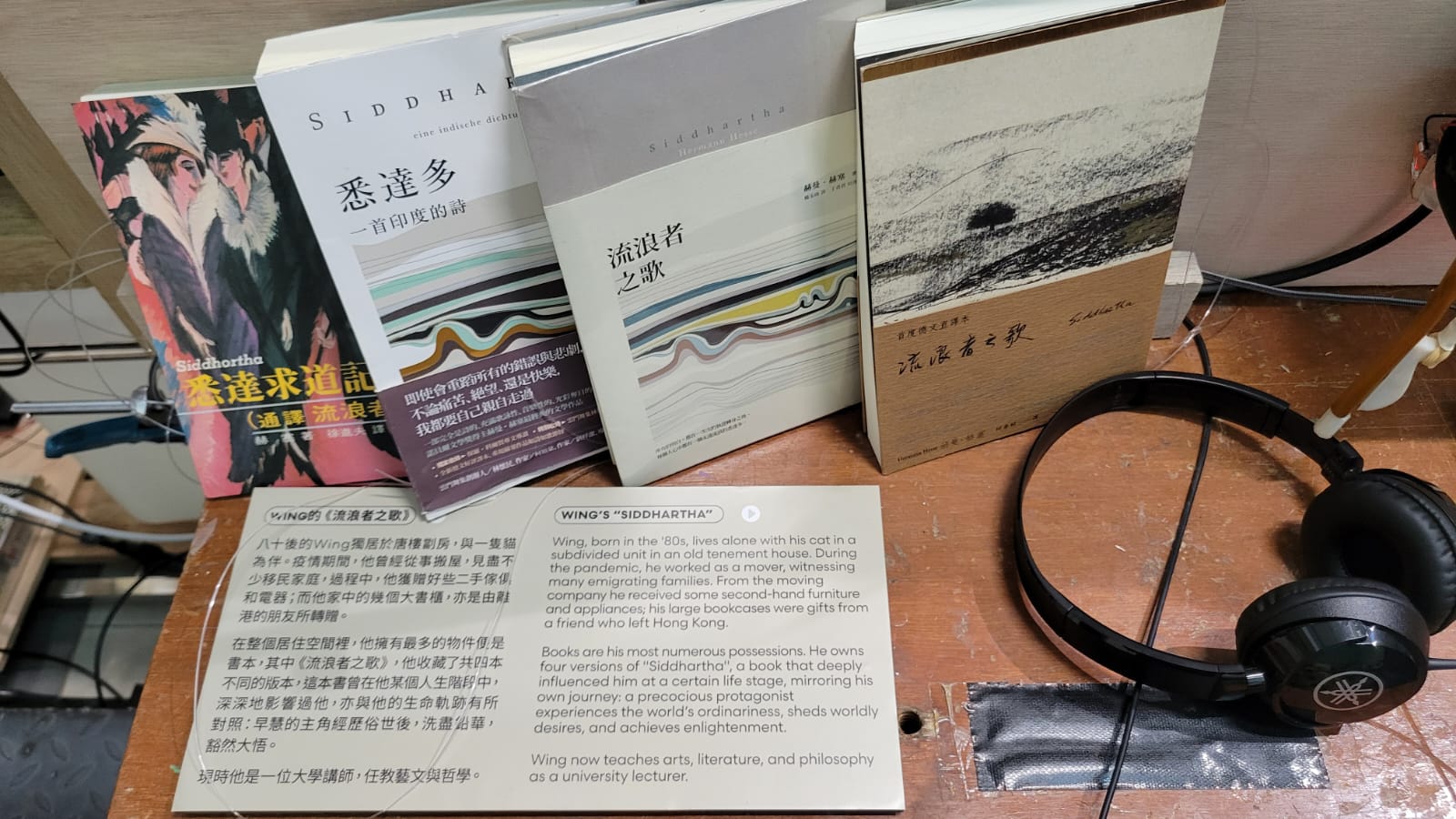

Jonathan:

Social impact assessment often feels theoretical. To make it accessible, I focus on tangible stories: What resources were invested? How many people were reached? What are the long-term goals? Clear, practical examples help people understand beyond the jargon.

Victoria:

That makes sense. Ultimately, you have to start with the basics—help people understand the concept first, in a language they understand—before introducing more complex ideas. As social sector practitioners, how should we continue to advocate for local adaptation of global concepts and language?

Jonathan:

The challenge is that while academics and practitioners understand these terms, the general public—and many in the business community—don’t. Our responsibility is to bridge that gap, thinking about our relationship with society, not just compliance. Ultimately, it’s about building a business case. In the case of neurodiversity, for example, as green industries grow, there’s a need for detail-oriented people—roles that neurodivergent individuals can excel in. When people see the value, they’re more open to inclusion, and language shifts accordingly. If you want inclusive environments, you have to change how you talk about the people you want to include.

What steps do you think we, as a sector, can take to move toward a shared language for social impact in Hong Kong? We invite your experiences and suggestions—let’s keep this conversation going and take action together.